On paper, it looked like a fantastic deal…

In 2017, the Chinese government offered to spend $100 million to build an ornate Chinese garden at the National Arboretum in Washington DC. Complete with temples, pavilions, and a 70-foot white pagoda, the project thrilled local officials, who hoped it would attract thousands of tourists every year.

But when US counterintelligence officials began digging into the details, they found numerous red flags. The pagoda, they noted, would have been strategically placed on one of the highest points in Washington DC, just two miles from the US Capitol, a perfect spot for signals intelligence collection, multiple sources familiar with the episode told CNN.

Also alarming was that Chinese officials wanted to build the pagoda with materials shipped to the US in diplomatic pouches, which US Customs officials are barred from examining, the sources said. Federal officials quietly killed the project before construction was underway. The canceled garden is part of a frenzy of counterintelligence activity by the FBI and other federal agencies focused on what career US security officials say has been a dramatic escalation of Chinese espionage on US soil over the past decade.

Since at least 2017, federal officials have investigated Chinese land purchases near critical infrastructure, shut down a high-profile regional consulate believed by the US government to be a hotbed of Chinese spies, and stonewalled what they saw as clear efforts to plant listening devices near sensitive military and government facilities.

Among the most alarming things, the FBI uncovered pertains to Chinese-made Huawei equipment atop cell towers near US military bases in the rural Midwest. According to multiple sources familiar with the matter, the FBI determined the equipment was capable of capturing and disrupting highly restricted Defense Department communications, including those used by US Strategic Command, which oversees the country’s nuclear weapons.

While broad concerns about Huawei equipment near US military installations have been well known, the existence of this investigation and its findings have never been reported. Its origins stretch back to at least the Obama administration. It was described to CNN by more than a dozen sources, including current and former national security officials. All of them spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

It’s unclear if the intelligence community determined whether any data was actually intercepted and sent back to Beijing from these towers. Sources familiar with the issue say that from a technical standpoint, it’s incredibly difficult to prove a given package of data was stolen and sent overseas.

The Chinese government strongly denies any efforts to spy on the US. Huawei in a statement to CNN also denied that its equipment is capable of operating in any communications spectrum allocated to the Defense Department.

But multiple sources familiar with the investigation tell CNN that there’s no question the Huawei equipment has the ability to intercept not only commercial cell traffic but also the highly restricted airwaves used by the military and disrupt critical US Strategic Command communications, giving the Chinese government a potential window into America’s nuclear arsenal.

“This gets into some of the most sensitive things we do,” said one former FBI official with knowledge of the investigation. “It would impact our ability for essentially command and control with the nuclear triad. “That goes into the ‘BFD’ category.”

“If it is possible for that to be disrupted, then that is a very bad day,” this person added.

Turning doves into hawks

Former officials described the probe’s findings as a watershed moment. The investigation was so secret that some senior policymakers in the White House and elsewhere in government weren’t briefed on its existence until 2019, according to two sources familiar with the matter.

That fall, the Federal Communications Commission initiated a rule that effectively banned small telecoms from using Huawei and a few other brands of Chinese made-equipment. ”The existence of the investigation at the highest levels turned some doves into hawks,” said one former US official.

In 2020, Congress approved $1.9 billion to remove Chinese-made Huawei and ZTE cellular technology across wide swaths of rural America. But two years later, none of that equipment has been removed and rural telecom companies are still waiting for federal reimbursement money. The FCC received applications to remove some 24,000 pieces of Chinese-made communications equipment—but according to a July 15 update from the commission, it is more than $3 billion short of the money it needs to reimburse all eligible companies.

Absent more money from Congress, the FCC says it plans to begin reimbursing approved companies for about 40 percent of the costs of removing Huawei equipment. The FCC did not specify a timeframe on when the money will be disbursed.

In late 2020, the Justice Department referred its national security concerns about Huawei equipment to the Commerce Department, and provided information on where the equipment was in place in the US, a former senior US law enforcement official told CNN.

After the Biden administration took office in 2021, the Commerce Department then opened its own probe into Huawei to determine if more urgent action was needed to expunge the Chinese technology provider from US telecom networks, the former law enforcement official and a current senior US official said.

That probe has proceeded slowly and is ongoing, the current US official said. Among the concerns that national security officials noted was that external communication from the Huawei equipment that occurs when software is updated, for example, could be exploited by the Chinese government.

Depending on what the Commerce Department finds, US telecom carriers could be forced to quickly remove Huawei equipment or face fines or other penalties.

Reuters first reported the existence of the Commerce Department probe.

“We cannot confirm or deny ongoing investigations, but we are committed to securing our information and communications technology and services supply chain. Protecting US persons safety and security against malign information collection is vital to protecting our economy and national security,” a Commerce Department spokesperson said.

US counterintelligence officials have recently made a priority of publicizing threats from China. This month, the US National Counterintelligence and Security Center issued a warning to American businesses and local and state governments about what it says are disguised efforts by China to manipulate them to influence US policy.

FBI Director Christopher Wray just traveled to London for a joint meeting with top British law enforcement officials to call attention to the Chinese threats.

In an exclusive interview with CNN, Wray said the FBI opens a new China counterintelligence investigation every 12 hours. “That’s probably about 2,000 or so investigations,” said Wray. “And that’s not even talking about their cyber theft, where they have a bigger hacking program than that of every other major nation combined, and have stolen more of Americans’ personal and corporate data than every nation combined.”

Asked why after years of national security concerns raised over Huawei, the equipment is still largely in place atop cell towers near US military bases, Wray said that, “We’re concerned about allowing any company that is beholden to a nation state that doesn’t adhere to and share our values, giving that company the ability to burrow into our telecommunications infrastructure.”

He noted that in 2020, the DOJ indicted Huawei with racketeering conspiracy and conspiracy to steal trade secrets.

“And I think that’s probably about all I can say on the topic,” said Wray.

Critics see xenophobic overreach

Despite its tough talk, the US government’s refusal to provide evidence to back up its claims that Huawei tech poses a risk to US national security has led some critics to accuse it of xenophobic overreach. The lack of a smoking gun also raises questions of whether US officials can separate legitimate Chinese investment from espionage.

“All of our products imported to the US have been tested and certified by the FCC before being deployed there,” Huawei said in its statement to CNN. “Our equipment only operates on the spectrum allocated by the FCC for commercial use. This means it cannot access any spectrum allocated to the DOD.”

“For more than 30 years, Huawei has maintained a proven track record in cyber security and we have never been involved in any malicious cyber security incidents,” the statement said.

In its zeal to sniff out evidence of Chinese spying, critics argue the feds have cast too wide a net – in particular as it relates to academic institutions. In one recent high-profile case, a federal judge acquitted a former University of Tennessee engineering professor whom the Justice Department had prosecuted under its so-called China Initiative that targets Chinese spying, arguing “there was no evidence presented that [the professor] ever collaborated with a Chinese university in conducting NASA-funded research.”

And on Jan. 20, the Justice Department dropped a separate case against an MIT professor accused of hiding his ties to China, saying it could no longer prove its case. In February, the Biden administration shut down the China Initiative entirely.

The federal government’s reticence across multiple administrations to detail what it knows has led some critics to accuse the government of chasing ghosts.

“It really comes down to: do you treat China as a neutral actor – because if you treat China as a neutral actor, then yeah, this seems crazy, that there’s some plot behind every tree,” said Anna Puglisi, a senior fellow at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology. “However, China has shown us through its policies and actions it is not a neutral actor.”

Chinese tech in the American heartland

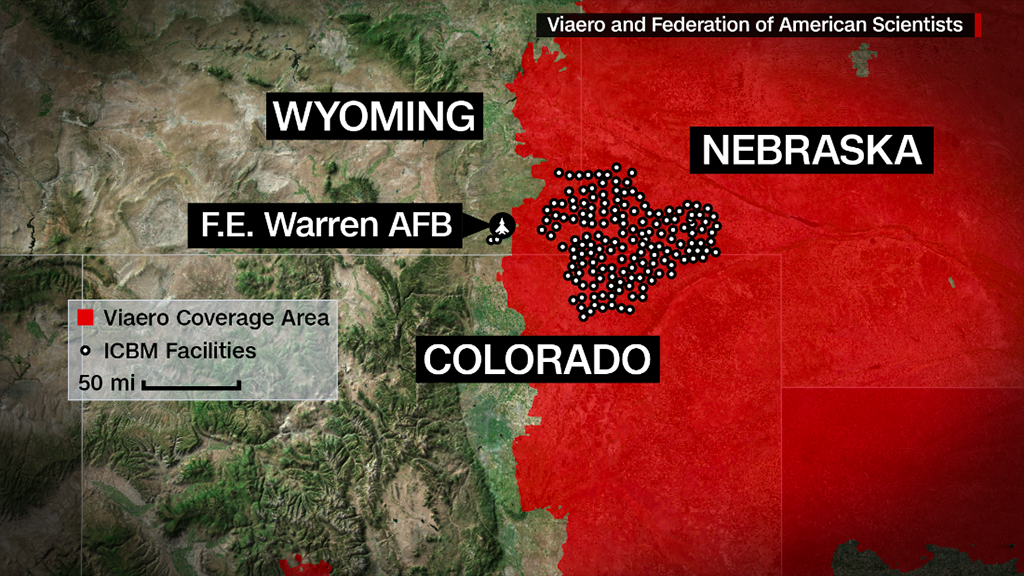

As early as the Obama administration, FBI agents were monitoring a disturbing pattern along stretches of Interstate 25 in Colorado and Montana, and on arteries into Nebraska. The heavily trafficked corridor connects some of the most secretive military installations in the US, including an archipelago of nuclear missile silos.

For years, small, rural telecom providers had been installing cheaper, Chinese-made routers and other technology atop cell towers up and down I-25 and elsewhere in the region. Across much of these sparsely populated swaths of the west, these smaller carriers are the only option for cell coverage. And many of them turned to Huawei for cheaper, reliable equipment.

Beginning in late 2011, Viaero, the largest regional provider in the area, inked a contract with Huawei to provide the equipment for its upgrade to 3G. A decade later, it has Huawei tech installed across its entire fleet of towers, roughly 1,000 spread over five western states.

As Huawei equipment began to proliferate near US military bases, federal investigators started taking notice, sources familiar with the matter told CNN. Of particular concern was that Huawei was routinely selling cheap equipment to rural providers in cases that appeared to be unprofitable for Huawei — but which placed its equipment near military assets.

Federal investigators initially began “examining [Huawei] less from a technical lens and more from a business/financial view,” explained John Lenkart, a former senior FBI agent focused on counterintelligence issues related to China. Officials studied where Huawei sales efforts were most concentrated and looked for deals that “made no sense from a return-on-investment perspective,” Lenkart said.

“A lot of [counterintelligence] concerns were uncovered based on” those searches, Lenkart said.

By examining the Huawei equipment themselves, FBI investigators determined it could recognize and disrupt DOD-spectrum communications - even though it had been certified by the FCC, according to a source familiar with the investigation.

“It’s not technically hard to make a device that complies with the FCC that listens to nonpublic bands but then is quietly waiting for some activation trigger to listen to other bands,” said Eduardo Rojas, who leads the radio spectrum lab at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida. “Technically, it’s feasible.”

To prove a device had clandestine capabilities, Rojas said, would require technical experts to strip down a device “to the semi-conductor level” and “reverse engineer the design.” But, he said, it can be done.

And there was another big concern along I-25, sources familiar with the investigation said.

Weather camera worries

Around 2014, Viaero started mounting high-definition surveillance cameras on its towers to live-stream weather and traffic, a public service it shared with local news organizations. With dozens of cameras posted up and down I-25, the cameras provided a 24-7 bird’s eye view of traffic and incoming weather, even providing advance warning of tornadoes.

But they were also inadvertently capturing the movement of US military equipment and personnel, giving Beijing — or anyone for that matter – the ability to track the pattern of activity between a series of closely guarded military facilities.

The intelligence community determined the publicly posted live-streams were being viewed and likely captured from China, according to three sources familiar with the matter. Two sources briefed on the investigation at the time said officials believed that it was possible for Beijing’s intelligence service to “task” the cameras – hack into the network and control where they pointed. At least some of the cameras in question were running on Huawei networks.

Viaero CEO Frank DiRico said it never occurred to him the cameras could be a national security risk.

“There’s a lot of missile silos in areas we cover. There is some military presence,” DiRico said in an interview from his Colorado office. But, he said, “I was never told to remove the equipment or to make any changes.”

In fact, DiRico first learned of government concerns about Huawei equipment from newspaper articles - not the FBI - and says he has never been briefed on the matter.

DiRico doesn’t question the government’s insistence that he needs to remove Huawei equipment, but he is skeptical that China’s intelligence services can exploit either the Huawei hardware itself or the camera equipment.

“We monitor our network pretty good,” DiRico said, adding that Viaero took over the support and maintenance for its own networks from Huawei shortly after installation. “We feel we’ve got a pretty good idea if there’s anything going on that’s inappropriate.”

Scouring the country for Chinese investments

By the time the I-25 investigation was briefed to the White House in 2019, counterintelligence officials begin looking for other places Chinese companies might be buying land or offering to develop a piece of municipal property, like a park or an old factory, sometimes as part of a “sister city” arrangement.

In one instance, officials shut down what they believed was a risky commercial deal near highly sensitive military testing installations in Utah sometime after the beginning of the I-25 investigation, according to one former US official. The military has a test and training range for hypersonic weapons in Utah, among other things. Sources declined to provide more details.

Federal officials were also alarmed by what sources described as a host of espionage and influence activities in Houston and, in 2020, shut down the Chinese consulate there.

Bill Evanina, who until early last year ran the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, told CNN that it can sometimes be hard to differentiate between a legitimate business opportunity and espionage — in part because both might be happening at the same time.

“What we’ve seen is legitimate companies that are three times removed from Beijing buy [a given] facility for obvious logical reasons, unaware of what the [Chinese] intelligence apparatus wants in that parcel [of land],” Evanina said. “What we’ve seen recently — it’s been what’s underneath the land.”

“The hard part is, that’s legitimate business, and what city or town is not going to want to take that money for that land when it’s just sitting there doing nothing?” he added.

A complicated problem

After the results of the I-25 investigation were briefed to the Trump White House in 2019, the FCC ordered that telecom companies who receive federal subsidies to provide cell service to remote areas — companies like Viaero — must “rip and replace” their Huawei and ZTE equipment.

The FCC has since said that the cost could be more than double the $1.9 billion appropriated in 2020 and absent an additional appropriation from Congress, the agency is only planning to reimburse companies for a fraction of their costs.

Given the staggering strategic risk, Lenkart said, “rip and replace is a very blunt and inefficient remediation.”

DiRico, the CEO of Viaero, said the cost of “rip and replace” is astronomical and that he doesn’t expect the reimbursement money to be enough to pay for the change. According to the FCC, Viaero is expected to receive less than half of the funding it is actually due. Still, he expects to start removing the equipment within the next year.

“It’s difficult and it’s a lot of money,” DiRico said.

Some former counterintelligence officials expressed frustration that the US government isn’t providing more granular detail about what it knows to companies — or to cities and states considering a Chinese investment proposal. They believe that not only would that kind of detail help private industry and state and local governments understand the seriousness of the threat as they see it, but also help combat the criticism that the US government is targeting Chinese companies and people, rather than Chinese state-run espionage.

“This government has to do a better job of letting everyone know this is a Communist Party issue, it’s not a Chinese people issue,” Evanina said. “And I’ll be the first to say that the government has to do better with respect to understanding the Communist Party’s intentions are not the same intentions of the Chinese people.”

A current FBI official said the bureau is giving more defensive briefings to US businesses, academic institutions and state and local governments that include far more detail than in the past, but officials are still fighting an uphill battle.

“Sometimes I feel like we’re a lifeguard going out to a drowning person, and they don’t want our help,” said the current FBI official. But, this person said, “I think sometimes we [the FBI] say ‘China threat,’ and we take for granted what all that means in our head. And it means something else to the people that we’re delivering it to.”

“I think we just need to be more careful about how we speak about it and educate folks on why we’re doing what we’re doing.”

In the meantime, the “rip and replace” program has remained fiercely controversial.

“It’s not going to be easy,” DiRico said. “I’m going to be up nights worrying about it, but we’ll do what we’re told to do.”