The US has lost at least three nuclear bombs that have never been located – they’re still out there to this day. How did this happen? Where could they be? And will we ever find them?

It was a mild winter’s morning at the height of the Cold War.

On January 17, 1966, at around 10:30 am, a Spanish shrimp fisherman watched a misshapen white parcel fall from the sky… and silently glide towards the Alboran Sea. It had something hanging beneath it, though he couldn’t make out what it was. Then it slipped beneath the waves.

At the same time, in the nearby fishing village of Palomares, locals looked up at an identical sky and witnessed a very different scene – two giant fireballs, hurtling toward them. Within seconds, the sleepy rural idyll was shattered. Buildings shook. Shrapnel sliced towards the ground. Body parts fell to the earth.

A few weeks later, Philip Meyers received a message via a teleprinter – a device a bit like a fax that could send and receive primitive emails. At the time, he was working as a bomb disposal officer at the Naval Air Facility Sigonella, in eastern Sicily. He was told that there was a top secret emergency in Spain and that he must report there within days.

However, the mission was not as covert as the military had hoped. “It was not a surprise to be called,” says Meyers. Even the public knew what was going on. When he attended a dinner party that evening and announced his mysterious trip, its intended confidentiality became something of a joke. “It was kind of embarrassing,” says Meyers. “It was supposed to be a secret but my friends were telling me why I was going.”

For weeks, newspapers around the globe had been reporting rumors of a terrible accident – two US military planes had collided in mid-air, scattering four B28 thermonuclear bombs across Palomares. Three were quickly recovered on land – but one had disappeared into the sparkling blue expanse to the southeast, lost to the bottom of the nearby swathe of Mediterranean Sea. Now the hunt was on to find it – along with its 1.1 megatonne warhead, with the explosive power of 1,100,000 tonnes of TNT.

An unknown number

In fact, the Palomares incident is not the only time a nuclear weapon has been misplaced. There have been at least 32 so-called “broken arrow” accidents – those involving these catastrophically destructive, earth-flattening devices – since 1950. In many cases, the weapons were dropped by mistake or jettisoned during an emergency, then later recovered. But three US bombs have gone missing altogether – they’re still out there to this day, lurking in swamps, fields and oceans across the planet.

“We mostly know about the American cases,” says Jeffrey Lewis, director of the East Asia Non-proliferation Program at the James Martin Center for Non-proliferation Studies, California. He explains that the full list only emerged when a summary prepared by the US Department of Defense was declassified in the 1980s.

Many occurred during the Cold War when the nation teetered on the precipice of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) with the Soviet Union – and consequently kept airplanes armed with nuclear weapons in the sky at all times from 1960 to 1968, in an operation known as Chrome Dome.

“We don’t know as much about other countries. We don’t really know anything about the United Kingdom or France, or Russia or China,” says Lewis. “So I don’t think we have anything like a full accounting.”

The Soviet Union’s nuclear past is particularly murky – it had amassed a stockpile of 45,000 nuclear weapons as of 1986. There are known cases where the country lost nuclear bombs that have never been retrieved, but unlike with the US incidents, they all occurred on submarines and their locations are known, if inaccessible.

One began on 8 April 1970, when a fire started spreading through the air conditioning system of a Soviet K-8 nuclear-powered submarine while it was diving in the Bay of Biscay – a treacherous stretch of water in the northeast Atlantic Ocean off the coasts of Spain and France, which is notorious for its violent storms and where many vessels have met their end. It had four nuclear torpedoes onboard, and when it promptly sank, it took its radioactive cargo with it.

However, these lost vessels didn’t always stay where they were. In 1974, a Soviet K-129 mysteriously sank in the Pacific Ocean northwest of Hawaii, along with three nuclear missiles. The US soon found out, and decided to mount a secret attempt to retrieve this nuclear prize, “which was really a pretty crazy story in and of itself”, says Lewis.

The eccentric American billionaire Howard Hughes, famous for his broad spectrum of activity, including as a pilot and film director, pretended to become interested in deep sea mining. “But in fact, it wasn’t deep sea mining, it was an effort to build this giant claw that could go all the way down to the sea floor, grab the submarine, and bring it back up,” says Lewis. This was Project Azorian – and unfortunately, it didn’t work. The submarine broke up as it was being lifted.

“And so those nuclear weapons would have fallen back to the sea floor,” says Lewis. The weapons remain there to this day, trapped in their rusting tomb. Some people think the weapons remain there to this day, trapped in their rusting tomb – though others believe they were eventually recovered.

Every now and then, there are reports that some of the US’ lost nuclear weapons have been found.

Back in 1998, a retired military officer and his partner were gripped with a sudden determination to discover a bomb dropped near Tybee Island, Georgia in 1958. They interviewed the pilot who had originally lost it, as well as those who had searched for the bomb all those decades ago – and narrowed down the search to Wassaw Sound, a nearby bay of the Atlantic Ocean. For years, the maverick duo scoured the area by boat, trailing a Geiger counter behind them to detect any tell-tale spikes in radiation.

And one day, there it was, in the exact spot the pilot had described – a patch with radiation 10 times the levels elsewhere. The government promptly dispatched a team to investigate. But alas, it was not the nuclear weapon. The anomaly was down to naturally occurring radiation from minerals in the seabed.

So for now, the US’ three lost hydrogen bombs – and, at the very least, a number of Soviet torpedoes – belong to the ocean, preserved as monuments to the risks of nuclear war, though they have largely been forgotten. Why haven’t we found all these rogue weapons yet? Is there a risk of them exploding? And will we ever get them back?

A shrouded object

When Meyers finally got to Palomares – the Spanish village where a B52 bomber came down in 1966 – the authorities were still looking for the missing nuclear bomb. Each night his team slept in tents in the village, which was freezing and damp. “It was just like an English winter,” he says. During the day they did very little – it was a waiting game.

“It’s a standard military thing, hurry up and wait,” says Meyers. “We had to rush over and then we did nothing for two weeks. And then after that, the undersea exploration became very serious.”

The search team enlisted the help of two ingenious inventions. One was an obscure theorem from the 18th Century invented by a Presbyterian minister-turned-amateur mathematician, which helps people to use information about past occurrences to calculate the probability of them happening again. They used this technique of “Bayesian inference” to decide where to look for the bomb, to help them search in the most efficient way possible and maximize their chances of finding it.

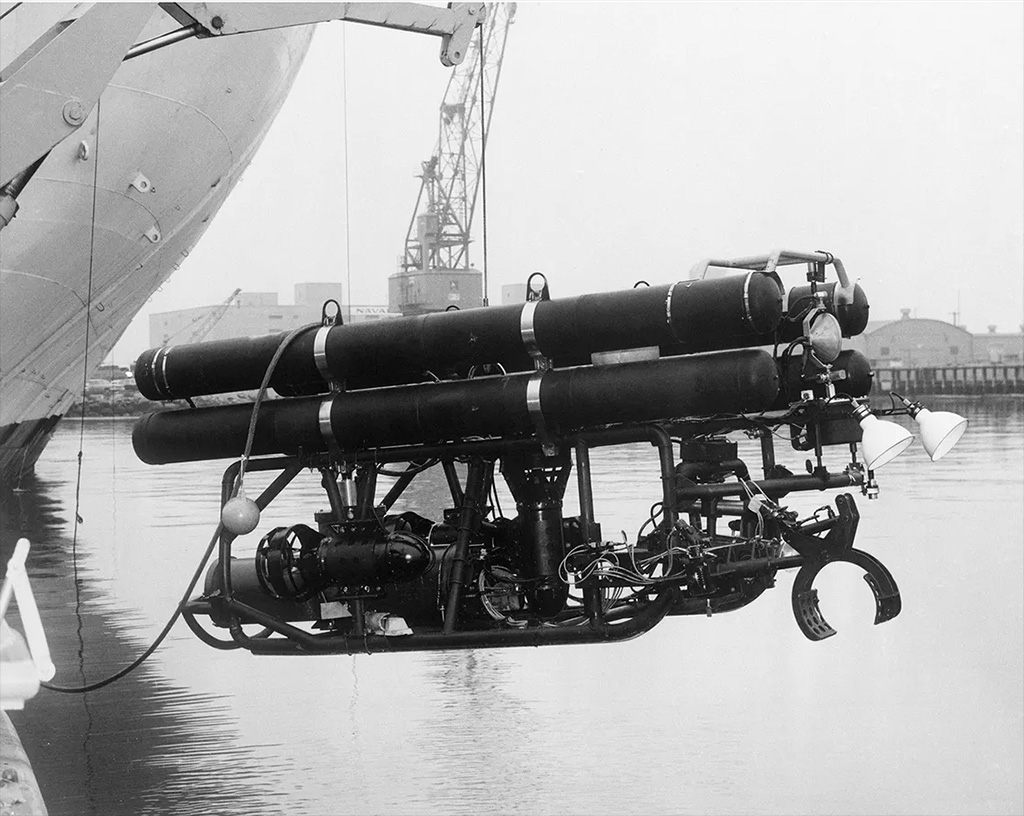

The second was “Alvin”, a cutting-edge deep-ocean submarine able to dive to unprecedented depths. Like a rotund white shark, each day, it descended into the deep blue Mediterranean water with a human crew in its belly and began a visual hunt.

On 1 March 1966, the little sub finally spotted something: a track made by the bomb when it first hit the sea bed. Later images revealed an eerie scene – the rounded tip of the missing nuclear weapon, covered by a ghostly shroud – its white parachute, which had partially deployed when it dropped, tangling itself up with its precious cargo. This deadly tube of metal had somehow ended up resembling a person dressed up for Halloween in a bedsheet.

But the struggle was not over. Now it was Meyers’ job to work out how to get this bomb off the ocean floor – where it sat 2,850ft (869m) deep. They improvised a kind of fishing line out of a few thousand feet of heavy-duty nylon rope and a metal hook – the idea was to latch onto the device, and pull it up until it was close enough to the surface that a diver could go down and secure it more thoroughly. “That was the plan. It didn’t work,” says Meyers.

“It was all done very deliberately and cautiously and slowly,” says Meyers. “So we just kind of waited around… we were anxious, wanting to see what do we do next when it comes up.” They managed to hook it onto the nuclear bomb and started to hoist it out of the water. They had lifted it up off the bottom when disaster struck. The parachute, resuscitated from its sleep on the ocean floor, suddenly began doing what they do best – slowing down its cargo’s speed, and making it harder to move.

“Do you realize that parachutes work just as well in water, as they do on land?” says Meyers. Eventually, the parachute was pulling so hard on the line and hook that it simply snapped – sending the nuclear bomb slowly gliding back down towards the bottom. This time, it ended up even deeper than before. (Little Alvin – with its human crew – only just managed to avoid becoming entangled and ending up on the bottom with it.)

Meyers was devastated. “It was extremely disappointing,” he says. With the bomb now less accessible than ever, his improvised line wouldn’t be long enough to catch it, so the task was handed over to another team, on another boat.

A month later they used a different kind of robotic submarine – a cable-controlled underwater vehicle – to grab the bomb by its parachute directly, and haul it up. It had shifted in its casing, so it couldn’t be disarmed the usual way, via a special port in the side – alarmingly, the officers instead had to cut into the nuclear weapon. “[It would have been] kind of nerve-wracking to drill a hole in a hydrogen bomb,” says Meyers. “But they did it. They were prepared to do that.”

A swampy mystery

Unfortunately, the three lost bombs still out there today did not meet with such successful recovery efforts. However, the risk of them causing a nuclear explosion is thought to be low.

To get to grips with why it helps to look at how nuclear bombs work.

In September 1905, Albert Einstein placed his fountain pen on the pages of his scientific paper, and scribbled down an idea that would become the world’s most famous equation. E = mc2, or energy equals an object’s mass multiplied by the speed of light squared. It means that each atom that makes up the world can be exchanged into energy, and vice versa. If you can work out how to do this, the release of energy is so explosive, it’s what powers the Sun.

Thirty-four years later, Einstein wrote to the US President, Franklin Roosevelt, to warn him that the Nazis were working on turning his theory into a weapon – and the rest is history. The Manhattan Project was rapidly formed, and in 1945 the US dropped its first nuclear weapon.

The bombs used on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and – a few days later – Nagasaki, were the original, atomic kind. These involved smashing the atoms of radioactive elements against each other, to cause them to split up and create different elements. This “fission” reaction releases so much energy, it causes other atoms to split in turn, until you end up with a massive, runaway reaction. The first time they were ever tested, scientists weren’t sure the reaction would ever stop – they considered the very real possibility that the world might end. (Read more about the moments that could have destroyed humanity.)

To achieve nuclear fission, atomic bombs usually involved a gun-like contraption that fired a hollow “bullet” of radioactive atoms such as uranium-235 into yet more uranium-235 or used conventional explosives to compress atoms of plutonium-239, until they started to split up. At Hiroshima and Nagasaki, these early weapons leveled the land for miles and killed hundreds of thousands of people, some of whom were vaporized in the blast zone and others who died of radiation burns or sickness in the days, months, and years afterward.

The next generation – the kind used in the 1950s and 60s, when the majority of the world’s lost nuclear weapons were misplaced – was thousands of times more powerful. These were thermonuclear, or hydrogen bombs and they involved a second nuclear reaction.

First, there was the usual fission step as with atomic bombs, which would release staggering amounts of energy. This would then ignite a second core, this time containing isotopes of hydrogen-deuterium (heavy hydrogen) and tritium (radioactive hydrogen) – which smash together and release even more energy when they fuse to form helium and one free neutron.

This system left room for a number of safety devices.

Take the lost Tybee island bomb, which is still lying in silt somewhere in Wassaw Sound. On February 5, 1958, this 7,600-pound (3,400-kg) Mark 15 thermonuclear weapon was loaded onto a B-47 bomber, which was about to join another B-47 on a long training mission. The idea was to simulate an attack on the Soviet Union, substituting the US town of Radford, Virginia, for Moscow. The pilots set off from Florida and crisscrossed their way to their target, as a way of testing their ability to fly with the heavy weapons onboard for hours at a time.

It all went well, but on the way back to the base, the planes encountered a separate training mission in South Carolina. This group’s plan was to intercept one of the B-47s – but there was a mix-up and they didn’t spot the second one, which was carrying the nuclear weapon. In the ensuing crash, the B-47 carrying the nuclear bomb was damaged.

The pilot decided to ditch the nuclear bomb into the water, then make an emergency landing. The bomb dropped 30,000ft (9,144m) into the water off Tybee Island – and even this impact didn’t detonate it. In fact, amazingly, none of the 32 broken arrow accidents have ever led to a detonation of nuclear components – though two have contaminated a wide area with radioactive material.

One possible factor in this lucky escape is a system of keeping the nuclear material needed for the fission reaction separate from the weapon itself. The capsule or “tip” – which in this case, consisted of plutonium – could then be added to the weapon at the last minute, when it was needed. This meant that, even if the weapon’s conventional explosives went off when it was onboard, the radioactive material wouldn’t get hot enough to actually do any atom-splitting.

Lewis also points out that, despite the Tybee bomb’s long journey from the sky to the ocean, the latter will have cushioned the blow – this is the same reason space capsules usually have “splashdown” landings rather than descending onto land.

Later bombs also included features such as “one point safety” – a way of making sure nuclear devices didn’t go off without being activated. In these weapons, the conventional explosives in a bomb might go off, but they wouldn’t detonate the radioactive material because this is squeezed out before it can be compressed. “If the explosive goes off, you want it to go off in an uneven way, if that’s not your goal – you want that plutonium to sort of squirt out,” says Lewis.

As it happens, having so many safety features is highly necessary – mostly because they don’t always work. In one case in 1961, a B-52 broke up while flying over Goldsboro, North Carolina, dropping two nuclear weapons to the ground. One was relatively undamaged after its parachute deployed successfully, but a later examination revealed that three out of four safeguards had failed.

In a declassified document from 1963, the then-US Secretary of Defence summed up the incident as a case where “by the slightest margin of chance, literally the failure of two wires to cross, a nuclear explosion was averted”.

The other nuclear bomb fell free to the ground, where it broke apart and ended up embedded in a field. Most parts were recovered, but one part containing uranium remains stuck under more than 50ft (15m) of mud. The US Air Force purchased the land around it to deter people from digging.

Some incidents are so baffling, they almost sound made up. Perhaps one of the most extraordinary occurred when a training exercise on the USS Ticonderoga went badly wrong in 1965. An A4E Skyhawk was being rolled to a plane elevator, while loaded with a B-43 nuclear bomb. It was a disaster in slow-motion – the crew on deck quickly realized that the plane was about to fall off, and waved for the pilot to apply the brakes. Tragically, he didn’t see them, and the young lieutenant, plane, and weapon vanished into the Philippine Sea. They’re still there to this day, under 16,000 ft (4,900 m) of water near a Japanese island.

A confused picture

Despite nearly 10 weeks of searching, the Tybee island bomb was declared irretrievably lost on the 16th of April 1958. According to a receipt written by the pilot who dropped it, the weapon did not contain the capsule – it wasn’t added before the training exercise. However, some people are concerned that this may not be correct. In 1966, the then-assistant to the Secretary of Defence wrote a letter in which he described the bomb as “complete” – i.e. containing its plutonium core. If this were true, the Mark 15 might still be capable of causing a full thermonuclear explosion.

Today the bomb is thought to be nestled under 5-15ft (1.5-4.6m) of silt on the seabed. In a final report on the weapon published in 2001, the Air Force Nuclear Weapons And Counterproliferation Agency concluded that if the conventional explosives inside are still intact, it could pose a “serious explosion hazard” to personnel and the environment – and is, therefore, best not disturbed, even by a recovery attempt.

But can a nuclear weapon explode underwater?

As it happens, it can. On 25 July 1946, the US detonated an atom bomb at the Bikini Atoll – a chain of postcard-perfect tropical islands surrounded by turquoise coral reefs, and beyond, the deep blue of the Pacific Ocean. They suspended the device 90ft (27m) below an assortment of ships filled with pigs and rats, and set it off. Several ships sank instantly, and the vast majority of the animals died – either from the initial blast or later of radiation poisoning. One striking image from that day shows the giant white mushroom cloud rising up like an alien weather formation, in front of a palm-fringed beach.

As a result of this and other tests, the island chain became so radioactive that plankton glowed on photographic plates. It’s still contaminated to this day – the people who once lived there have never been able to return, though like Chernobyl it has become an oasis for wildlife.

A permanent loss

Lewis thinks it’s unlikely that we will ever find the three missing nuclear bombs. This is partly down to the same reasons they weren’t found in the first place.

One is that they’re usually located via a visual search – and this is extremely difficult.

When planes crash into the ocean, the black box is often found days or weeks later by officials looking to piece together what happened. This might give the impression that it’s easy to find such objects in these vast swathes of water with modern technology. But they have a secret that helps this process along – an “underwater location beacon”, which guides search teams towards them with a repeating electronic pulse.

The lost nuclear weapons came with no such equipment. Instead, teams must narrow down a search area, then scour the ocean bit by bit – a tedious and inefficient process, which requires human divers or submarines.

An alternative would be to look for spikes in radiation, as the retired military officer Derek Duke did in his search for the Tybee bomb. But this is also extremely tricky – partly because nuclear bombs are not actually particularly radioactive.

“They’re designed not to be a radioactive threat to the people handling them,” says Lewis. “So they do have a radioactive signature, but it’s just not very significant – you have to be fairly close.”

In 1989, another Soviet nuclear submarine, the K-278 Komsomolets, sank in the Barents Sea off the coast of Norway. Like the K-8, it was also nuclear-powered, and it had been carrying two nuclear torpedoes at the time. For decades, its wreck has been lying under a mile (1.7km) of Arctic water.

But in 2019, scientists visited the vessel – and revealed that water samples taken from its ventilation pipe contained radiation levels up to 100,000 times higher than would normally be expected in seawater. However, this is unusual. It’s thought that radioactive elements from its nuclear reactor – as opposed to its nuclear torpedoes – are leaking out through this vent, possibly due to a rupture from when it crashed. Just half a meter (1.6ft) further away from the pipe, the isotopes were so diluted, radiation levels were normal.

For Lewis, the fascination with lost nuclear weapons isn’t the potential risks they pose now – it’s what they represent: the fragility of our seemingly sophisticated systems for handling dangerous inventions safely.

“I think we have this fantasy that the people who handle nuclear weapons are somehow different than all the other people we know, make fewer mistakes, or that they’re somehow smarter. But the reality is that the organizations that we have to handle nuclear weapons are like every other human organization. They make mistakes. They’re imperfect,” says Lewis.

Even at Palomares, where all the nuclear bombs that were dropped were eventually recovered, the land is still contaminated with radiation from two that detonated with conventional explosives. Some of the US military personnel who helped with the initial clean-up efforts – involving shoveling the surface of the soil into barrels – have since developed mysterious cancers which they believe are linked. In 2020, a number of survivors filed a class action suit against the Secretary of Veterans Affairs – though many of the claimants are currently in their late 70s and 80s.

Meanwhile, the local community has been campaigning for a more thorough clean-up for decades. Palomares has been dubbed “the most radioactive town in Europe”, and local environmentalists are currently protesting against a British company’s plans to build a holiday resort in the area.

Lewis is confident that losses of the kind that occurred during the Cold War are unlikely to happen again, mostly because operation Chrome Dome ended in 1968, and planes carrying nuclear bombs no longer fly around on regular training exercises. “Airborne alerts ended for reasons that must be obvious to us,” he says. “In the end, the decision was made that it was too dangerous.”

The exception to this progress is, of course, nuclear submarines – and even today, there are near-misses. The US currently has 14 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) in operation, while France and the UK have four each.

To work as nuclear deterrents these submarines must remain undetected during operations at sea, and this means they can’t send any signals to the surface to find out where they are. Instead, they must navigate mostly by inertia – essentially, the crew relies on machines equipped with gyroscopes to calculate where the submarine is at any given time based on where it was last, what direction it was headed and how fast it was traveling. This potentially imprecise system has resulted in a number of incidents, including as recently as 2018 when a British SSBN almost bumped into a ferry.

The era of lost nuclear weapons might not be over just yet.